Paper icons

The collection of religious engravings of the Museum of Byzantine Culture is among the most significant collections of the kind on an international level. It contains 239 engravings and 10 wooden and copper engraving plates. The 232 engravings and the 8 plates come from the personal collection of Dori Papastratou. The collection was a donation of the collector herself that was completed by her daughters Marina and Daphne in 1995. Several of the works in the collection have been presented in Greek and foreign exhibitions and publications.

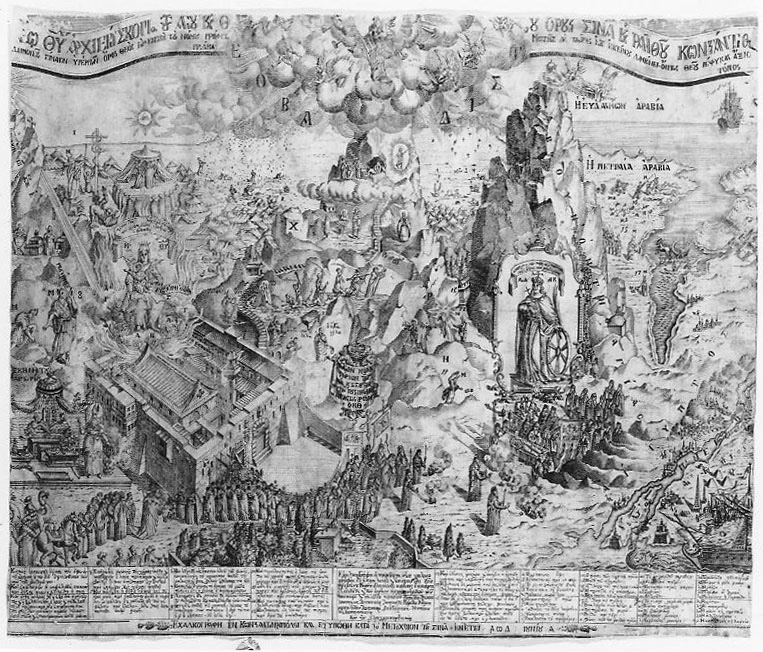

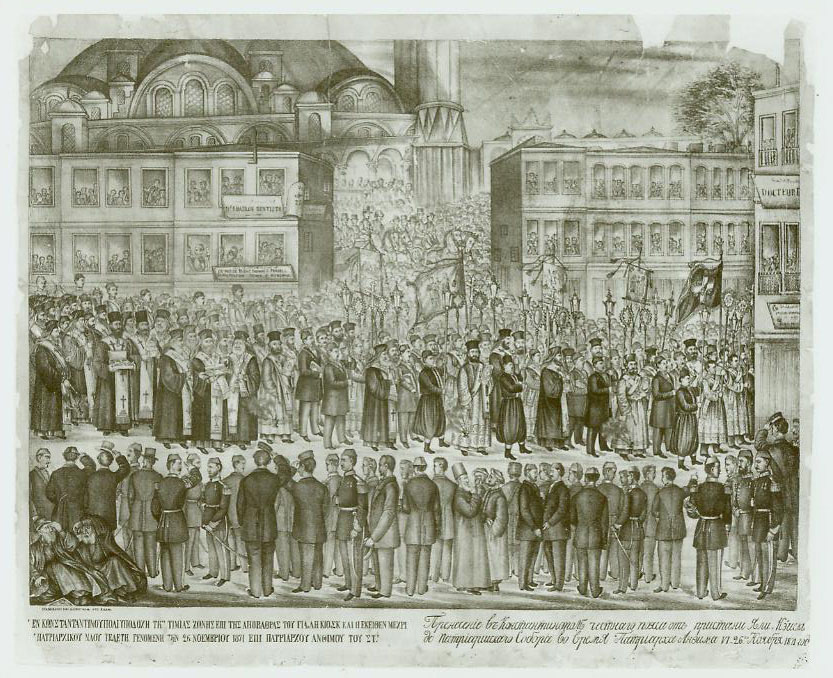

The collection of the Museum contains religious engravings, which are also called paper icons. These represent an almost unknown aspect of the Orthodox iconography, as they have a parallel development with the wall-paintings and the portable icons. Initially, paper icons were imported by the metropolitan centers of Europe (Venice, Vienna etc). The starting point of the Orthodox print-making is placed in 17th century; at first, wood-cuts were produced, later on, from the 18th to the early 20th centuries, etchings and in the end lithographs. The prints were made and circulated in the Orthodox communities of the areas under the Ottoman dominion and the communities abroad. They represent holy figures, religious scenes and panoramic views of monasteries, of the Mount Athos, the Mount Sinai, and elsewhere; views of churches with the patron Saints and secondary scenes with scenes of the Saints’ lives. Some of them come from prayer-books, which are influenced by the Renaissance views of cities that often decorate the Western illustrated travelogues and prayer-books. In the Museum’s collection there are also antimins and indulgences. In its largest part the collection consists of engravings made in Mount Athos by hieromonks, monks and laymen engravers and goldsmithers, whose majority had a workshop in Karyes, the capital of the monastic community of Mount Athos. On the prints there are inscriptions that mention the names of their creators; these sometimes are identified with their print-makers (stampadourous), or some others with their sponsors. One plate used to produce thousand of low lost prints; these were printed on paper, or on silk. The prints were distributed to the pilgrims on the Holy celebrations of the monasteries and churches in picture, which, in this way, became widely known.